Death Of The Two-Piece: Does The Suit Have A Future After Covid?

How times change. Back in 2018, the three-Michelin star chef Dabiz Munoz reported, somewhat dumbfounded, that he was not allowed into an unnamed London club for a meeting with a financier. Why? Because he wasn’t wearing a suit. Post-Covid, with talk of office blocks shuttering and surveys suggesting a majority of people now want to work from home for the best part of each week, it would be hard to find someone in a suit. Small wonder formalwear businesses have been crippled, and even esteemed Savile Row tailors closed for good.

This follows two of the most influential, macro of trends to reshape menswear over the last 20 years too. Firstly there’s the break-down in workplace dress codes, itself mirroring a break down in conventional workplace hierarchies. A 2019 study revealed that just one in 10 British workers wears a suit to work, with three-quarters of them dressing down not just on Fridays, but every day. They prefer it that way too: it’s cheaper, more comfortable and creates a more relaxed working atmosphere. And then there’s the fundamental shift at the heart of work in the 21st century towards freelancing, the gig economy, a blurring of work and leisure time and even big business’ need to present a more approachable image.

Business casual has quickly become the de facto dress code for modern organisations, as epitomised by the likes of Canali.

If the suit is no longer expected attire outside of all but the most conservative of careers, in some quarters it’s actually frowned on – symbolic of stuffiness and a lack of youthful dynamism. Even the Institute of Directors has introduced a ‘smart casual’ dress code. The G8 meeting of world leaders has also encouraged more dressing down in a bid to foster a more “intimate and informal” atmosphere. Corporate monoliths JP Morgan and PwC have followed.

Secondly, there has been the influence of streetwear – once an age-bracketed niche, now, in effect, since its pioneers have grown up and won positions of power, accounting for the majority of menswear; and then this has been followed by the coup de grace to formality that has come in the guise of athleisure: the wholesale appropriation of sportswear – functional, comfortable, progressive – as everyday wear. That, of course, is a trend that’s only benefited further by the pandemic lockdowns.

The rise of athleisure means you’re more likely to see modern men in matching tailored sweats, like these from Brunello Cucinelli, than a traditional two-piece.

So things look very bad for the suit, right? Well, maybe. Certainly makers of formalwear argue that there will always be some kind of occasion for the structured suit, because people will always love the idea of dressing up for an an event – though, purely anecdotally, the claim that men are now choosing to wear a suit to go out seems demonstrably false, unless it’s to go to a high-end restaurant or the opera. And that’s not often enough to sustain the style, even in ‘normal’ times.

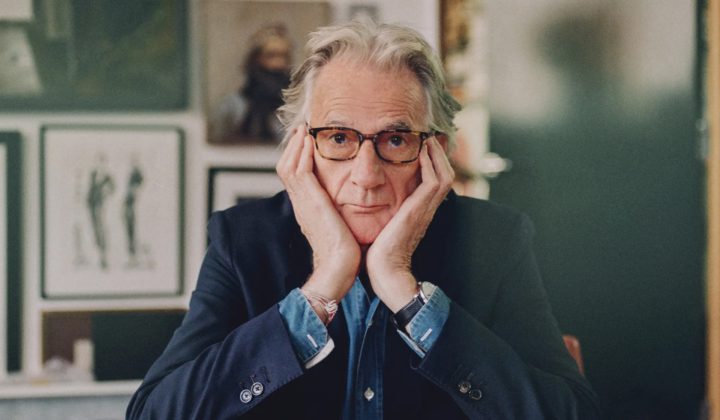

Rather, as renowned tailor Richard James has argued, it’s the suit itself that is going to have to change if it’s to survive. It’s going to need to be softer and lighter, in large part a product of the choice of cloths, with mills now making more woven blends to provide a more slouchy, cardigan-like ease, with more natural stretch but also shape retention and even water-repellency. It’s a touch of formality with plenty of functionality. In other words, the Suit 2.0 is athleisure with a better cut. Or, it’s completely re-booted as a high-fashion item, subject to the same waxing and waning of trends.

The Suit 2.0 is likely going to be much more slouchy and relaxed. The type of cuts Italian tailors such as Boglioli have long been renowned for.

The suit still makes its red carpet appearances, but not in a form that would cut it in any boardroom: look at those bold colours and soft pastels, crushed velvets and other off-piste fabrics, the big patterns, asymmetric cuts and raglan sleeves, Velcro fastenings and pull-over jackets. The top and bottom halves go together, but that’s about all that makes these looks suits in the traditional sense.

Such adventurous approaches to dressing ask how a suit in the 21st century might actually be defined, and make us consider what a suit is actually for. A suit is clearly no longer the utilitarian, 9-5 garment it evolved to become. Perhaps now it’s function is simply to signal that respect for the occasion is being paid, without the need to fit into any pre-conceptions regarding sobriety or restraint. This is not the kind of suit that our grandfathers would recognise. Not even our fathers. It’s hard to imagine today’s teens ever wearing a suit of the kind that has for so long been a staple of menswear.

Savile Row tailors are worried that the demand for bespoke tailoring may never recover.

Bespoke tailoring, Gieves & Hawkes’ Creative Director, John Harrison, has argued, will remain, but more as part of that niche, trainspottery interest in craft more broadly. He’s asked lots of pertinent questions: why do suit jackets have lapels, for example? Why is a working cuff still something to get excited about? These are historic artefacts and surely there’s scope for a much more minimalistic, modernistic take.

The effects of Covid on how we dress may seem trivial in the context of the very human disaster, but might actually prove to be one of its more enduring impacts, finally making comfort and functionality the key drivers in the clothes we wear, rather than characteristics we have to secretly crave only once we’ve ticked the ‘fashion’ box. And the most likely victim of that is the suit, reborn as something that chimes with the times.

The suit is dead. Long live the new suit.