In From The Wilderness: The Return Of The Safari Jacket

It would be easy to conclude that the safari jacket has long since gone the way of its matching headwear, the pith helmet. So associated is it with the stereotype of the Great White Hunter – with all that suggests of colonialism and the killing of endangered animals, neither great choices in more aware times – that it would be hard to imagine it having a place in fashion.

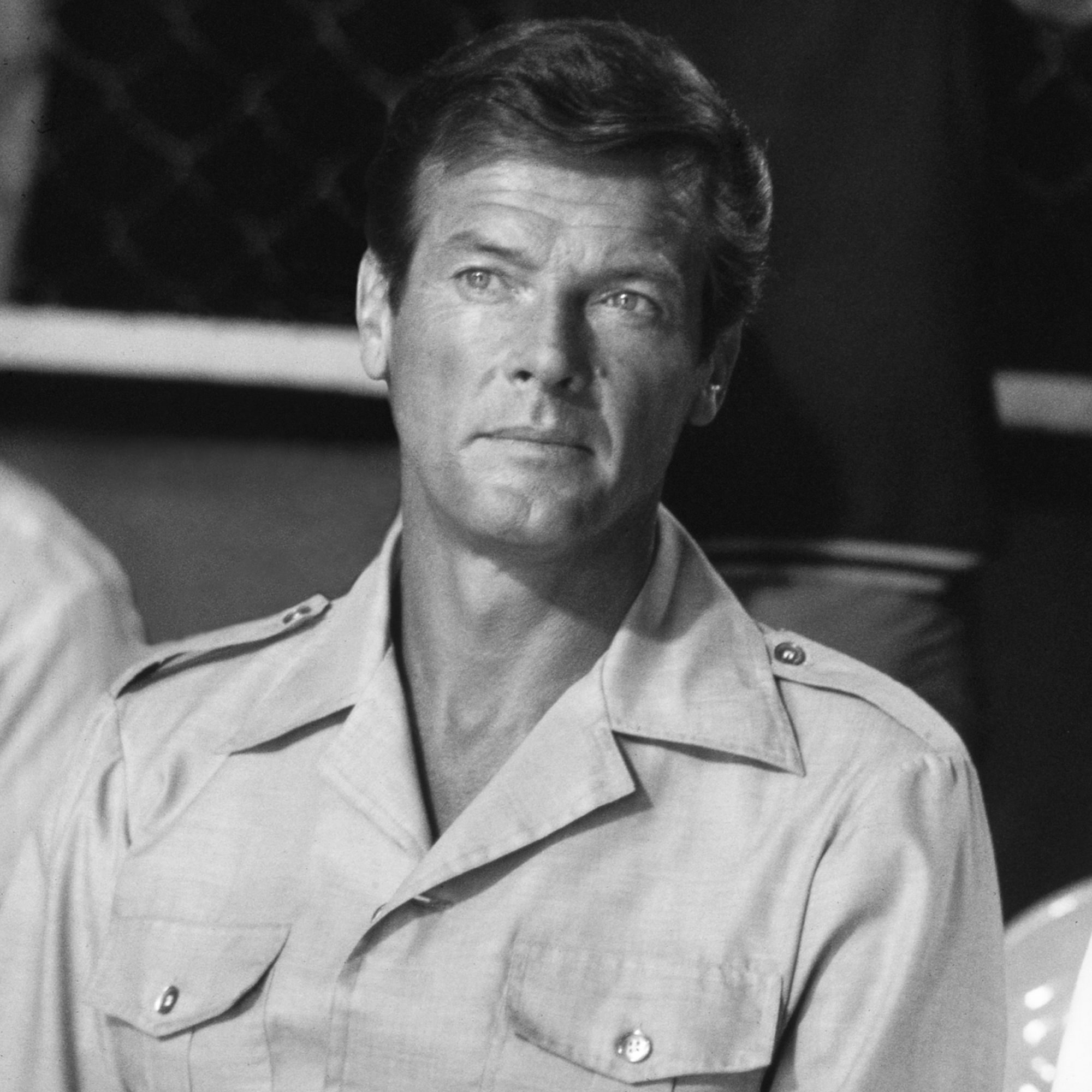

All the same, it crawls back from out of the bush periodically to make a statement: designers Ted Lapidus and then Yves Saint Laurent made it tres chic in the late 1960s (Saint Laurent’s African collection of 1967 saw the style reinvented initially for women) while Roger Moore sported one in his first outing as James Bond in Live and Let Die (albeit in navy wool), and in the more traditional cream or tan in another three of the Bond movie series. Moore had actually helped popularise the style – in cream suede, no less – before Bond, in his role in The Persuaders.

Roger Moore as James Bond wearing a safari jacket in The Man With The Golden Gun (1974)

In these fantasies, of course, the jacket – this lightweight, hardy style characterised by its open collar, epaulettes, belt and four box-pleat patch pockets – suited the more exotic locales. Picture wearing one down your local high street – even one from a masculine brand like Dunhill, Ralph Lauren or Richard James – and it’s another matter.

And yet there is something ineffably cool about the safari jacket, even if it’s on a more urban safari. Yes, it walks like a panther along the fine line between camp and macho – the former group would include Kenneth Halliwell, who, his lover Joe Orton noted, “looked as though he was going to do a number called ‘Jungle Drums’ [in his safari jacket]”, and those street hustlers who always seemed to be wearing a safari jacket in Starsky and Hutch. In the latter group would be the leading men who wore the style in any number of post-war movies based around African adventures, from Road to Zanzibar (1941), to Safari (1956), to Hatari! (1962). What else would Mr Macho himself, Ernest Hemingway, wear while out on his hunting trips?

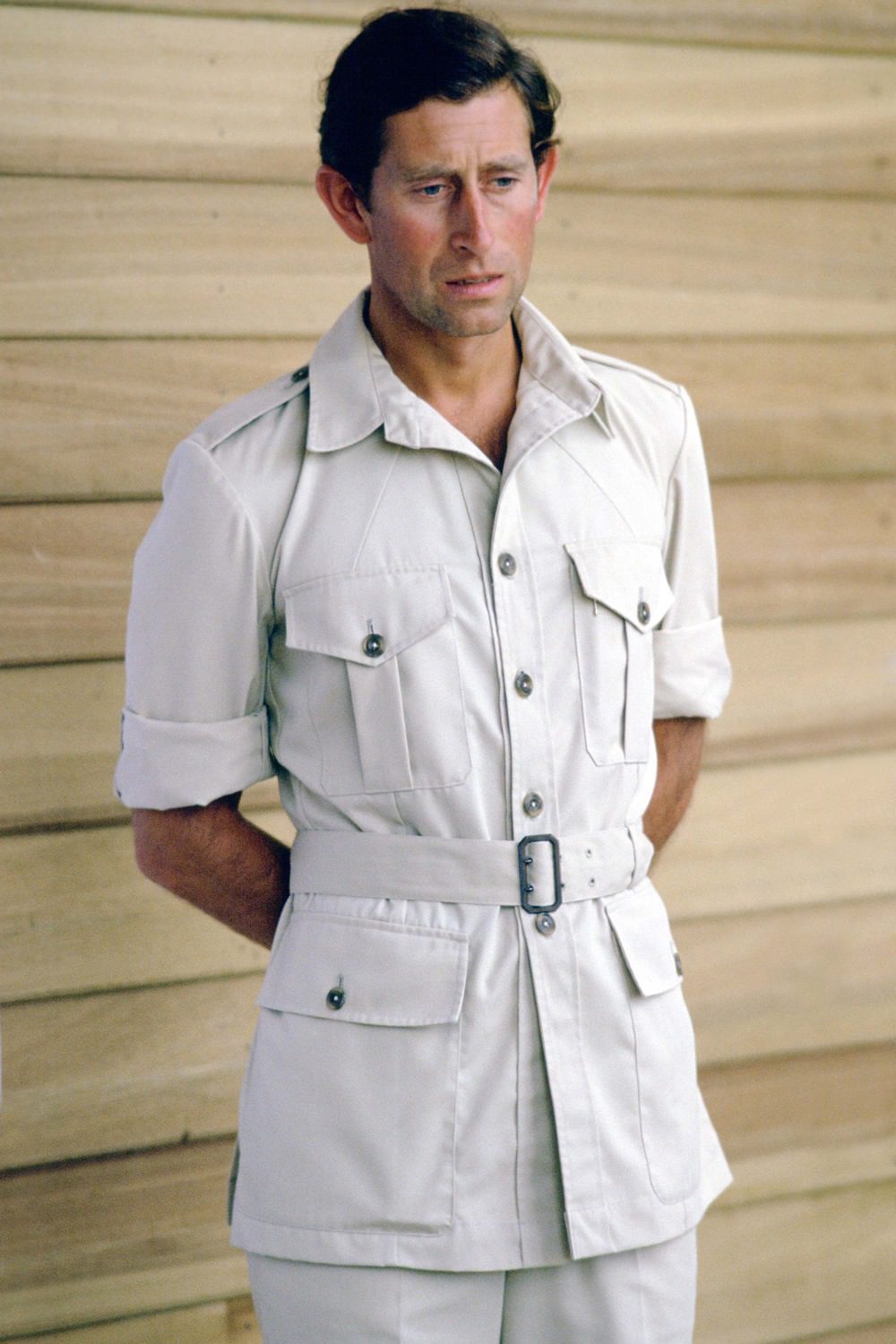

Then again, there was a pre-war time when, if one was wealthy enough to go to far-flung places the likes of Africa then a safari jacket is what one had one’s tailor knock up. That’s what Edward VIII did in the 1920s. It’s what Winston Churchill did too.

The Prince of Wales has long been a fan of the safari jacket in tropical climes

And no wonder really. The safari jacket is, after all, an eminently practical form of dress, being, in effect, a hot-weather version of the classic military garment, the field jacket; take the same jacket and make it in a waxed cotton, and it’s a trials biker jacket from the likes of Belstaff or Barbour. The classic version comes in that sandy beige colour – like that of khakis, which take their name from the Urdu for “dun-coloured” – providing a kind of simple camouflage while also hiding the dirt. In cotton drill, linen or tropical weave blend it breathes well under a hot sun and in tropical climes. The belt draws the jacket in, helping ensure that the wearer doesn’t get caught up in his clothing while facing off with a pissed-off bull elephant, if one of those happens to be marauding down said high street. And, all those pockets allow him to travel light, which in turn ensures he could hold his rifle ready to shoot. Or, you know, has somewhere to put his phone and cardholder.

Indeed, for a time in the 1960s, the safari jacket – worn with matching trousers, as part of a safari suit – became tropical India’s answer to the formal business suit. Natwar Singh, then a young diplomat, recalled returning from the UN to join PM Indira Gandhi’s secretariat with six colleagues. “Seven out of seven of us wore safari suits – that’s how common they were,” he reported. India’s pre-eminent cricketer of the era, Sunil Gavaskar, also modelled them in advertisements.

A modern suede safari jacket by Brunello Cucinelli

But the secret to wearing a safari jacket today is precisely not to think of it as a smart garment at all, but a rough and tough, go anywhere piece for men who like their clothing functional. Wear a safari jacket tailored and pristine – with a cravat and trousers with a slight kick flare – and you’re definitely risking opprobrium walking into a pub. Wear one crumpled and battered – over a chambray work shirt or white T-shirt, with a pair of selvedge jeans – and you simply look ready for anything. The safari jacket loses those Great White Hunter connotations and becomes a summer version of the field jacket. “Safari” means “journey” and here’s the ideal garment to wear on one. It’s the perfect travel jacket: comfortable, multi-pocketed and getting better with age.

Perhaps only one version of the safari jacket is beyond the pale, and that’s the short-sleeved design. Of course, this makes perfect sense if you really are on safari – and can keep your tongue firmly in cheek – but in all other scenarios there’s just something too “fancy dress” about it. Unless, of course, you’re Stewart Grainger in King Solomon’s Mines, playing the character Allan Quartermain, a kind of James Bond before James Bond. And then, well, it just looks totally badass.